On the subject of things that fly by, back in the mists of time when this blog was new and still finding its place in the blogosphere I did a short post about the announcement of a new challenger for the World Land Speed Record. Since then of course Eclectic Ephemera has evolved into the vintage-centric site it is today, but on Thursday the successful test-firing in Newquay of the proposed 1,000mph Bloodhound SSC's rocket engine captured my imagination all over again and inspired this post - which will look at the past holders of the Land Speed Record from those decades of greatest endeavour, the ones we all know and love: the 1920s and '30s.

In the early years of the motor car at the turn of the last century the speed record increased dramatically in quite a short space of time rising from the initial 41mph (!) in 1898, to 76mph four years later and then up to a heady 126mph in 1909. The record was to stay at this level for nearly 16 years until a flurry of new attempts were made. In a car that has featured in these pages before, Welshman John Parry Thomas drove to 171mph on Pendine Sands in south Wales in 1926.

|

| Henry Segrave |

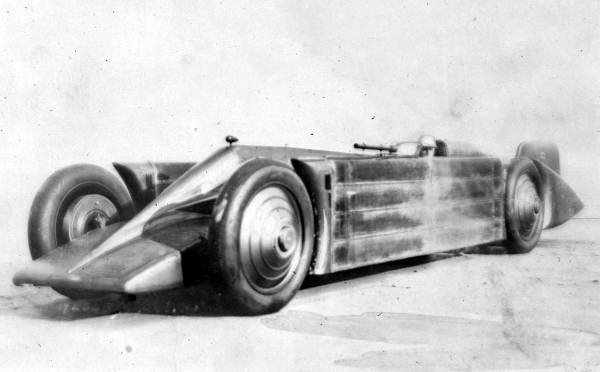

Specifically designed to achieve the "double ton" the Sunbeam 1000hp set the template for the speed cars that followed it. Powered by two 22.4-litre Sunbeam V12 aeroplane engines (one in front of the driver and one behind) "The Slug" actually produced nearer 900hp, still more than enough to meet the challenge. It also featured then-novel streamlined all-encompassing bodywork designed to reduce wind resistance. The tyres had to be specially designed to withstand the planned 200+mph speed - that must have seemed so unbelievable and untested at the time - but even so were only rated for 3½-minutes of use at top speed.

1,000 H.P CAR

Setting a precedent that would be followed for almost a decade, out of necessity for a course with a long enough run, Segrave took the Sunbeam to Daytona Beach in Florida. There, on the 29th March 1927, he set a new average Land Speed Record of 203.79mph - at one point recorded travelling as fast as 211mph - thereby becoming the first person (and "The Slug" the first car) to travel at more than 200mph on land.

Two years later, following two successful attempts by Malcolm Campbell and American Ray Keech, the record stood at an only slightly faster 207.55mph. Keen to reclaim the record for Britain, Segrave commissioned an all-new speed car. For my money one of the most beautiful vehicles to have held the record, Golden Arrow was developed by ex-Sunbeam designer J. S. Irving. Powered by a single 23.9-litre Napier Lion W12 aero engine, exactly the same as could be found in the Schneider Trophy-winning racing seaplanes of the time, it had 925hp on tap. While hardly much more than "The Slug" had, Golden Arrow's almost Art Deco bodywork was made from lightweight aluminium, especially constructed by the famous coachbuilding firm of Thrupp & Maberly.

SPEED KING'S TRIUMPH 231 MILES AN HOUR

Almost 2 years to the day he first went over 200mph, Segrave returned to Daytona beach on the 11th March 1929. Amazingly he undertook only one test run before going for the record, which he comprehensively smashed with an average speed of 231.45mph, a fantastic feat that helped earn him a knighthood. Following his run, however, Segrave was witness to a tragically fatal crash involving the American challenger (Lee Bible in the previous record holder, Ray Keech's, Triplex Special) and a photographer. Vowing never to attempt the Land Speed Record again, Segrave - also an avid speedboat racer - turned his attention to the Water Speed Record. As a result of this, Golden Arrow was never used again. It still holds the record for the least-travelled speed car, having covered a mere 18.74 miles. Both it and "The Slug" can be seen today at the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu, Hampshire.

Sadly the Water Speed Record proved to be no safer for Sir Henry Segrave. He attempted to capture it in his boat Miss England II at Lake Windermere on Friday 13th June 1930, a matter of months after he was accorded his knighthood. Unfortunately during one run the boat is thought to have hit a log and capsized. Mechanic Michael "Jack" Willcocks was thrown clear and suffered only a broken arm, but chief engineer Victor Halliwell was killed instantly; Segrave was knocked unconscious and gravely hurt. He was rescued and brought ashore, regained consciousness for long enough to learn the fate of "his men" - and that he had broken the Water Speed Record thereby becoming the first man to hold both land and water speed records simultaneously - but sadly succumbed to his injuries shortly thereafter. His name however lives on in the form of the Segrave Trophy.

The name that is perhaps most closely associated with land and water speed records, though, is that of Campbell. Malcolm Campbell was also an ex-RAF racing driver and first broke the Land Speed Record in 1924 (clocking 150.76mph), at Pendine Sands, in a 350hp V12 Sunbeam racing car - the first of his Blue Birds (now on show at Beaulieu).

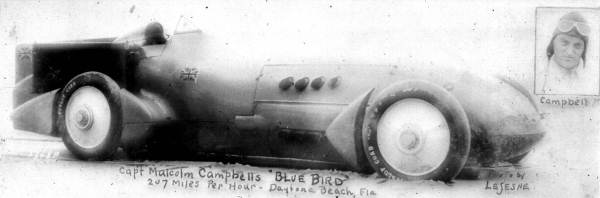

At around the same time as Segrave was going for the LSR in 1927 Campbell was readying his own entry, the second Blue Bird. This too would use the same Napier Lion engine as Segrave's later Golden Arrow, although in an earlier state of tune and putting out barely half the Arrow's power - 500hp to be exact. It also lacked the aerodynamic bodywork of Segrave's Sunbeam 1000hp, still resembling more the standard race car design of the day. Despite this it was able to average 174.88mph (on one run going as high as 195mph) on the 4th February 1927, a month before Segrave passed 200mph.

Spurred on by this competition Campbell had Blue Bird II rebuilt for 1928 and managed to get hold of Napier engine in "Sprint" tune - that is, exactly the same as was used in Schneider Trophy seaplanes and as Segrave would fit to Golden Arrow. This meant around 900hp, almost double the original Bluebird II. Streamlining and aerodynamics were also applied for the first time, as the bodywork was completely redesigned. Like Segrave's Sunbeam 1000hp this was undertaken by another famous coachbuilder - Mulliner. On the 19th February 1928, having followed Segrave's lead and headed to Daytona Beach, Campbell and Blue Bird III hit 206.956mph, just beating Segrave's record.

Spurred on by this competition Campbell had Blue Bird II rebuilt for 1928 and managed to get hold of Napier engine in "Sprint" tune - that is, exactly the same as was used in Schneider Trophy seaplanes and as Segrave would fit to Golden Arrow. This meant around 900hp, almost double the original Bluebird II. Streamlining and aerodynamics were also applied for the first time, as the bodywork was completely redesigned. Like Segrave's Sunbeam 1000hp this was undertaken by another famous coachbuilder - Mulliner. On the 19th February 1928, having followed Segrave's lead and headed to Daytona Beach, Campbell and Blue Bird III hit 206.956mph, just beating Segrave's record.Following the American Ray Keech and then Segrave's incredible 231mph, Campbell realised a whole new car was required if he was to have any hope of beating the record again. He enlisted the help of experienced designer Reid Railton, who would go on to have much success developing speed cars for Campbell and others. Taking inspiration from Segrave, Railton and Campbell fitted bodywork that included a vertical stabilising fin as first seen on Golden Arrow. To make sure of trumping that car they shoehorned in a supercharged 23.9-litre Napier Lion aero engine, which put out 1,450hp - half as much again as Golden Arrow and twice the power of Blue Bird III. With this new (and slightly wordy!) Napier-Campbell-Railton Blue Bird Campbell once again returned to Daytona Beach in 1931 (having first unsuccessfully tested a possible alternative site in South Africa) and succeeded in setting a new LSR of 246mph. A year later he raised it further to over 250mph with the same car on the same course.

WORLD'S SPEED RECORD BROKEN

253.96 MILES PER HOUR!

Another year later, in 1933, and Blue Bird had been rebuilt again. Externally little changed, but beneath the bodywork sat a new V12 Rolls-Royce R aero engine (the precursor to the Merlin and also used in the newest Schneider seaplanes) with an unbelievable capacity of 33.9 litres and 2,300hp. This allowed the Campbell-Railton Blue Bird, as it was now known, to easily surpass the existing record and post a new sped of 272mph. The 300mph mark was getting tantalisingly close.

CAMPBELL SETS NEW SPEED MARK!

SIR MALCOLM CAMPBELL'S TRIUMPH

To achieve the desired 300mph, Campbell and Railton spent two years redesigning Blue Bird again - focussing on the bodywork, which developed into a delightful '30s Modernist streamline, and various mechanical upgrades (including the wheels, which were doubled at the rear for more grip). In 1935 the updated Blue Bird went first at to 276.82mph at Daytona and, with that course's limit fast being reached, Campbell moved to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah - still the home of high speed events today. There, on the 3rd Septemeber 1935, Campbell was able to squeeze Blue Bird to 301mph. Having become the first man to travel over 300mph on land, being knighted for his efforts, Campbell went after the Water Speed Record as well and had much success in that arena too. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Campbell survived to die of natural causes (a series of strokes) aged 63 in 1948.

Campbell would live long enough to see his land speed record broken a further five times by two different men. Captain George Eyston and John Cobb took up the mantle laid down by Segrave and Campbell earlier in the 1930s. Eyston was the first to break Cambell's record in 1937 with his monster speed car, Thunderbolt.

CAPTAIN GEORGE EYSTON'S NEW CAR

Thunderbolt was by far and away the most incredible car to hold the LSR between the wars. In order to go faster than Blue Bird's 301mph Eyston fitted not one supercharged Rolls-Royce R engine, but two. With each engine 36½ litres and producing 2,350hp, Thunderbolt had 72 litres and 4,700hp on tap(!). However, it also weighed 7 tons, twice as much as any other speed car. Nevertheless on the 19th November 1937 Eyston set the record at 312mph and the following year, on the 27th August 1938, improved on it to the tune of 345.5mph.

Much as with Segrave and Campbell Eyston and Cobb competed against each other for the LSR, sometimes at the same event. Such was the case on the 15th September 1938. Cobb had worked with Reid Railton to design his entry for the WSR and the result was the gorgeous Railton Special, a lithe streamlined shape that would remain virtually unchanged in the world of the LSR for nearly 30 years. While it used two older supercharged Napier Lion W12 engines rather than the newer Rolls-Royce R engines found in Thunderbolt, its power deficit was made up by the extensive use of lightweight aluminium in the body.

NEW LAND SPEED RECORD

So it was that both cars were at Bonneville in September 1938. Eyston looked on as Cobb took the Special to 353.3mph. The next day he promptly jumped in to Thunderbolt and raised the record again to 357.5mph. Eyston and Thunderbolt held on to the record for almost one year until the 23rd August 1939, only 10 days before the outbreak of the Second World War, Cobb returned to Utah with the Special and became the last pre-war holder of the Land Speed Record, managing 369.7mph. Eyston never challenged for the record again, although like Campbell he lived well in to old age dying in Lambeth in 1979 at the age of 81. Sadly Thunderbolt, after being shown in Australia and New Zealand during the war (including at the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition from 1939 to 1940), was destroyed in a warehouse fire. A surviving spare Napier engine that was used in the car can be seen at the Science Museum, however.

Cobb would return to the Salt Flats one last time in 1947. The Special was rebuilt with the aid of oil company Mobil, becoming the Railton Mobil Special. On the 16th of September that year Cobb pushed the record up yet further. Although on one measured run the Special broke the 400mph barrier (becoming the first land vehicle to do so) the mile-each-way average speed was a frustratingly close 394.19mph. Even so it would stand for almost 20 years until a new generation of Campbell and Blue Bird - Malcolm's son Donald and Blue Bird CN7 - came along to draw down the curtain on wheel-driven land speed record cars, tipping it over the 400 mark by 3mph. Cobb would not live to see this as he also died attempting the Water Speed Record, at Loch Ness on the 29th September 1952. The Railton Mobil Special now resides at the Thinktank museum in Birmingham.

Although the holders of the official Land Speed Record have all since been jet- and/or rocket-propelled there is still something thrilling and affirming about man's attempts to go ever faster [on land]. I can still remember that October day in 1997 when ThrustSSC became the first ground-based vehicle to pass through the sound barrier. Much is rightly being made about the Bloodhound project's influence on and encouragement of future engineers and the ongoing desire to push the boundaries of man and machine. In those respects I suspect it is no different from 80-odd years ago. I can't wait to be thrilled again when Wing Commander Andy Green attempts to better his own record with a frankly astonishing 1,000mph target speed. Good luck, Team Bloodhound!

You certainly know your motoring history, super post. Captain Hastings would be salivating.

ReplyDelete